»Please try to remember that what they believe, as well as what they do and cause you to endure does not testify to your inferiority but to their inhumanity«.

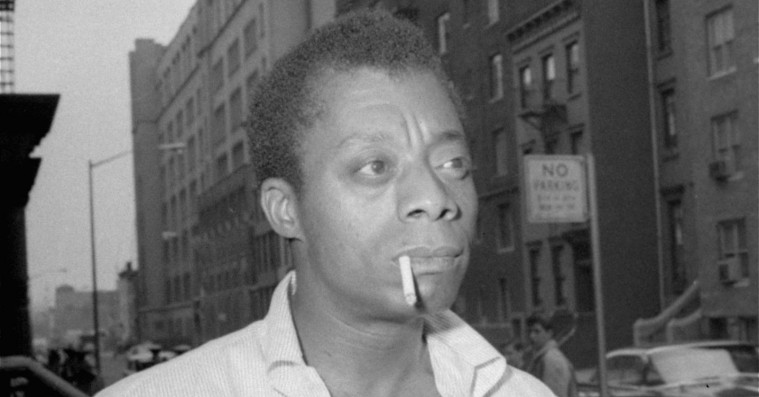

– James Baldwin, ‘The Fire Next Time’

I first met the work of Baldwin when I was 12 years-old and living in the small twin-island nation in the Caribbean – Trinidad and Tobago. An avid reader, I was looking through my Uncle John’s books when I stumbled across a worn-paperback of ‘If Beale Street Could Talk’. The story takes place in Harlem in the 1970s and chronicles the love between Fonny and Tish, and how that love is challenged when Fonny is falsely accused of rape.

I’ll never forget the feeling that overcame me as I read the book under the hot Caribbean sun. I had moved to Trinidad from Brooklyn only two years before, and the world of which he wrote was familiar to me. In fact, just a few years before I had written a short story in Brooklyn – I was just ten – about a young couple who learned that the main female character was pregnant. In Brooklyn, teenage pregnancy was present. When I flipped to the back of the book and saw his iconic face – I immediately set off to learn more about this man.

Like so many others, Baldwin became my mentor, my friend, my mother, my father. He was my go-to guide in life and my comfort. He helped me navigate the slippery slope of questioning my religion – Christianity – and put words and order to the world I had been born into.

For too many of us whose lives have been damaged by the ravages of European colonialism and the enslavement of our ancestors, there was a need for humanitarian heroes, a hunger for those who look the devil in the eyes and proclaim, loudly, eloquently: »You are indeed a monster«.

What resonated most profoundly for me and many others about Baldwin is that he had managed to leave the United States of America to live in Paris, among other places. Wrapped up in this migration is a hope that many Blacks harbor – that of escaping white American racism. Further reading of any of his over 20 books and countless essays taught us, his starving young fan base, that the peace that is longed to be experienced in Europe is all too easily punctured. He taught us about the colonial relationship of France towards Algeria and reminded us, lest we forget, that Europe is indeed the birthplace of racism.

When I was a young publishing professional in New York during the 90s, every other Black writer I came across had pretty much the same experience with Baldwin. Although he wrote in a period decades before our existence, we found the topics that he touched upon still painfully relevant: racism and white America’s inability to confront it. Baldwin spoke about difficult subjects in a beautiful language.

He was a Black, queer man – and not ashamed of it. In fact, he saw his queerness as an integral component of his art and political and social message. These things were not separate for him.

His 1956 novel, ‘Giovanni’s Room’, was groundbreaking in that Baldwin not only put queerness at the center of his novel, but interestingly took Blackness out: The main characters in this novel were white.

When we think about power and representation it is important to point out this crucial fact when reviewing his work. Baldwin is not just a pioneer in speaking truth to power regarding race, but the lived experiences of what it means to be queer, For a Black man to write a Queer novel with no major Black characters in the late 50s is indeed radical. It is perhaps this novel that endeared me the most to him; if just for the very fact that he demonstrates his own literary power and takes me to a place I would otherwise never know. This is the power of art and literature.

No matter what work of Baldwin’s you pick up, you will experience the passion and the fury from which he writes. What is indeed most saddening to me is how relevant his work is, still.

One of the best-kept secrets in the United States is that freedom has yet to come to the descendants of enslaved Africans. This you learn well even if you do not want to learn it. You learn that segregation continues, under a different language, a different guise. If you are privileged enough to travel, as I have been, you learn that the vast majority of neighborhoods in the U.S. are still mostly, exclusively white. You learn whose lives are valued and whose are not, whose lives matter – this information is now brought straight into our homes via social media and videos of assassinations of our men, women and children.

You learn that as a queer Black person, your existence is preferred invisible and that there is little protection for your life. You learn that the woman who accused Emmett Till, the 14 year old who was brutally lynched in Mississippi in 1955, just a year before ‘Giovanni’s Room’ was published, admitted to lying about the whole case and that she is still alive and free, as well as the fact that his murderers were never convicted. It was this dead, black boy’s body that sparked the Civil Rights Movement.

You learn that although we are in 2017, in the supposed Decade of People of the African Descent, that Blacks throughout the diaspora, whether in rubber boats attempting to flee poverty or coming in via international airports, travel at great risk: both from the elements of nature and from governments.

You learn that in the United States of America and now increasingly around the world, locking up Black bodies continues to be a way of racialized control, an unbroken continuity of chattel slavery and a result of hundreds of years of white supremacist doctrine which remains the number one narrative of the west, still relatively unchallenged wherever you go.

There is not much to give hope these days. I speak to you as a Black woman, who chose to leave the brutality of white racism in the United States of America for a softer, more blunt but no less damaging racism experienced here in Europe.

My only wish this evening is that when you watch this film, that you attempt not to place the distance of perceived time between the events which are touched upon in this film and the present. No. I ask that you reckon with that which your ancestors have refused to deal and which is now your inheritance. And where we go now is entirely up to how you deal with this continued and unnecessary dilemma.

Læs også: Alle vores CPH:DOX-anmeldelser samlet på ét sted